If you read the multitude of blogs out there Campaigns rarely last for more than a year or two before either the players get bored or the GM gets burnout. My last attempt at a Megadungeon was to convert Dungeon Crawl Classic #51 Castle Whiterock and that lasted for two levels before the group disbanded due to some moving away, others not able to schedule game time in due to real life commitments. This hasn’t stopped me from wanting to run an epic megadungeon game which is why I’ve been slowly coming up with a fantasy setting that takes place completely underground.

Planning my Megadungeon

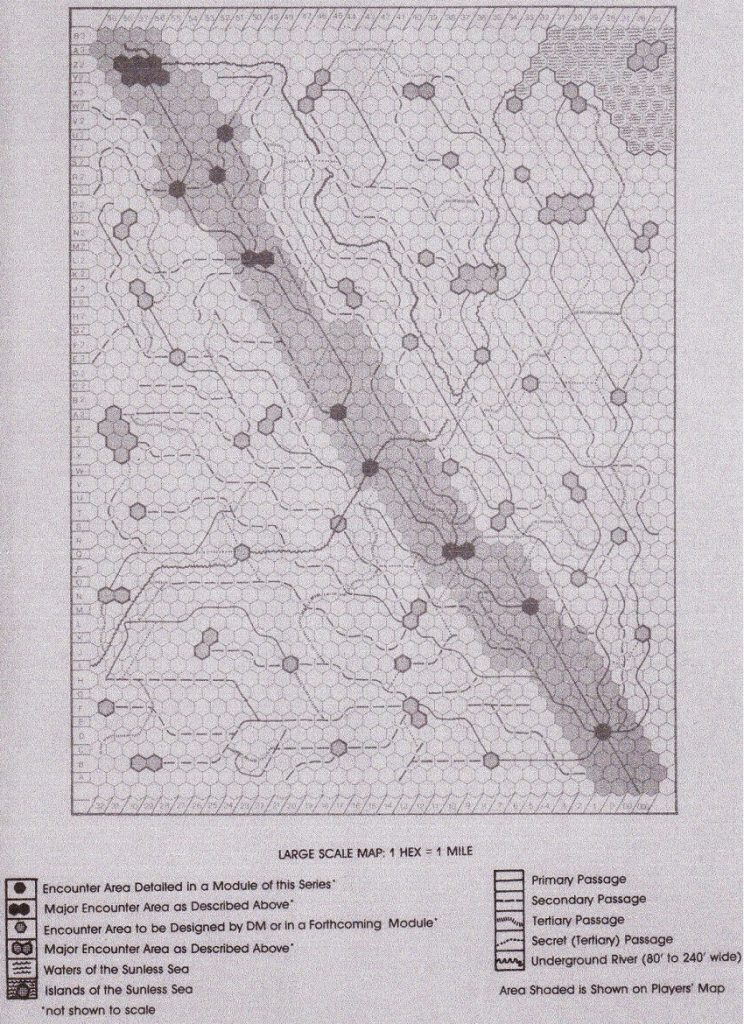

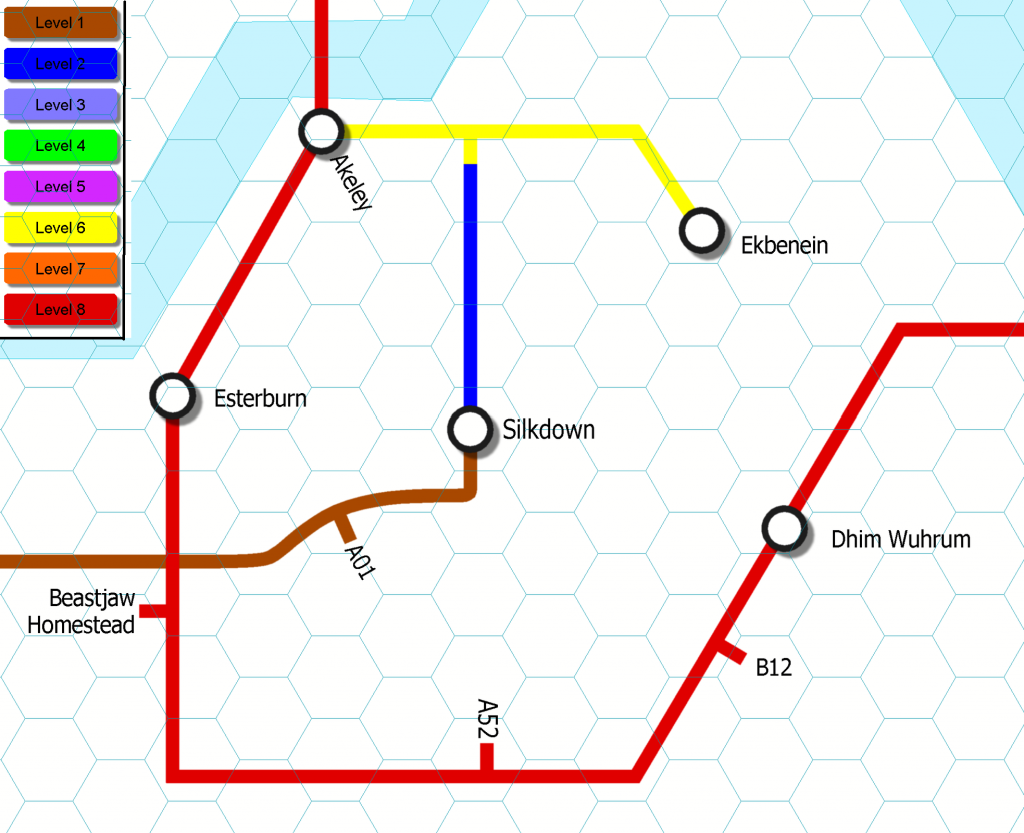

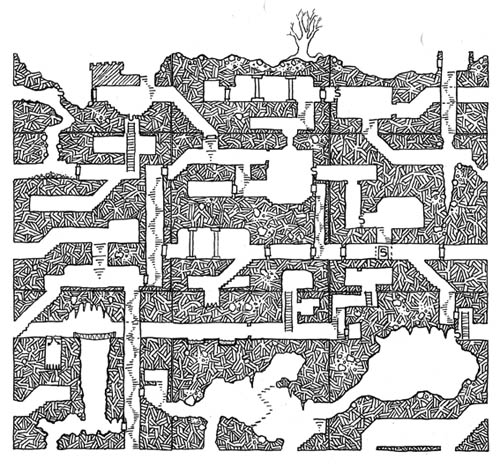

If my Megadungeon is endless then I should make some kind of “overland” map to get an idea of where the players may be heading so I know what lies ahead (or below). I first got the idea of using a Transit Style map for a quick abstract guide back in 2010 with Profantasy Softwares May 2010 Annual “Abstract Maps”. I was pretty pleased with myself until I realised that Gary Gygax had done almost the same thing in 1978 (two years before I discovered D&D) with Dungeon Module D1 Descent Into the Depths of the Earth.

Gygax came up with an easy system, much like a transit map, of showing the players where they were in relation to where they have been, albeit in an abstract form. This frees up the GM from having to make miles of rooms and corridors that will never get explored. Each “transit line” would represent the main route, whether it is a long winding cavern, a massively wide corridor, or a tiny one yard wide passage. Along the indicated route you have marker points that represent either encounter points, Burrows (Residential Towns), or large campaign size dungeon. This doesn’t mean that there is nothing between point A and point B. It just means the players will not be mapping and exploring those points at this time.

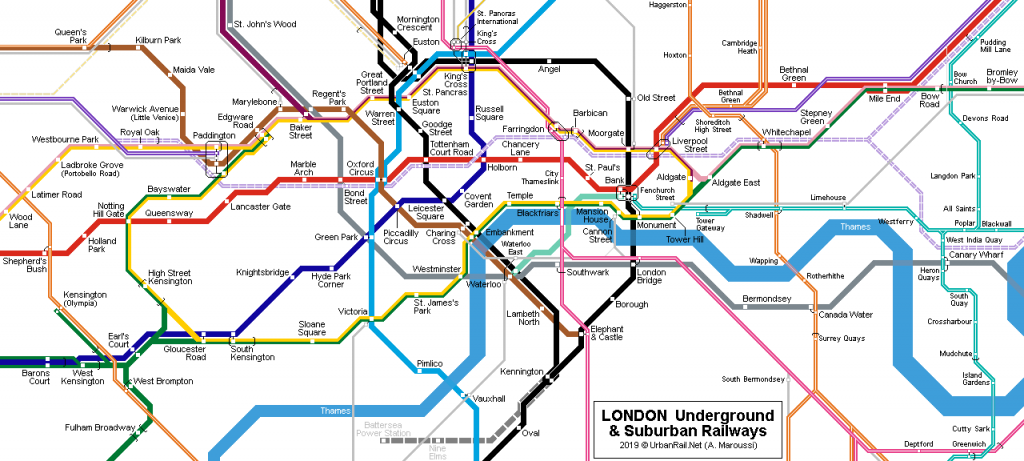

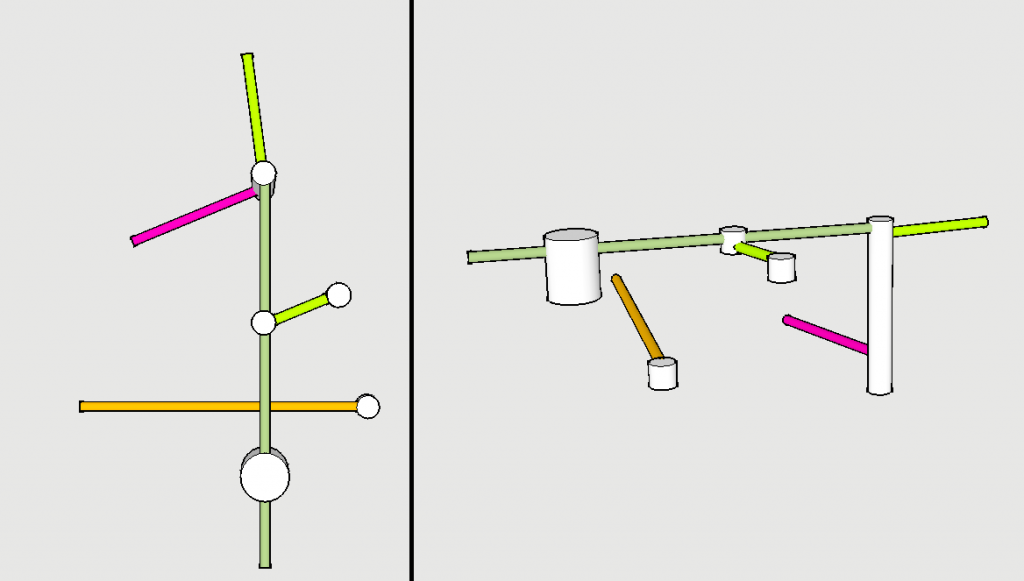

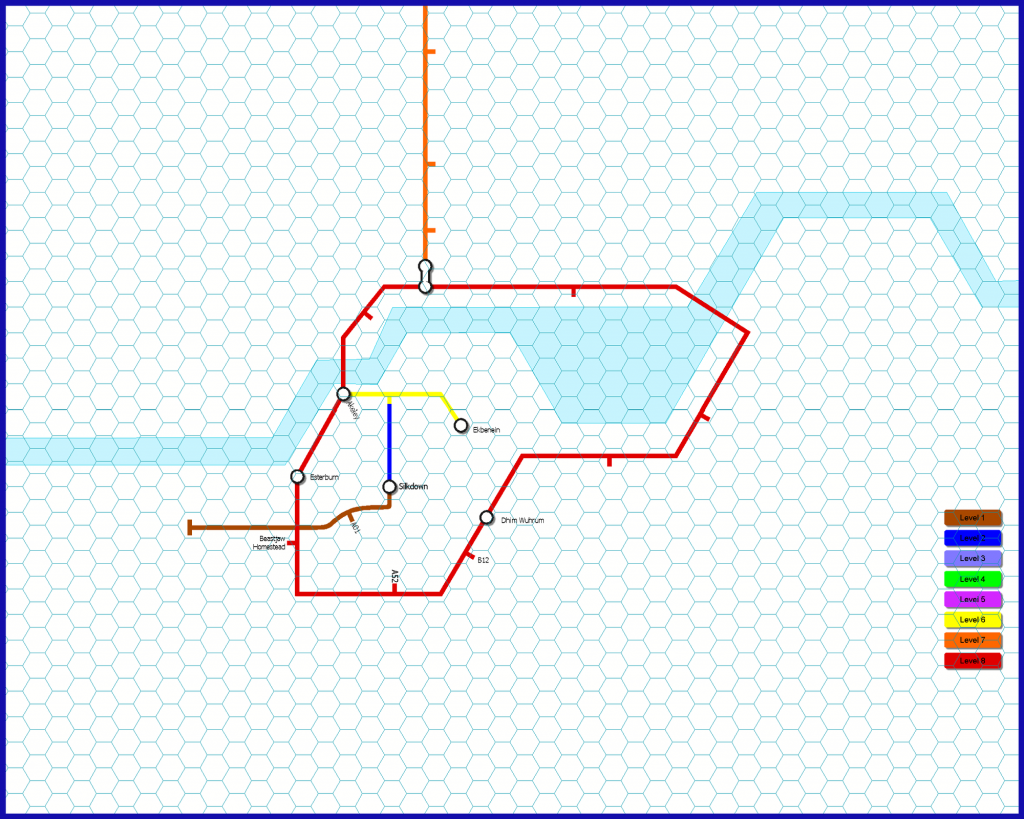

Now on a transit map, which now has a pretty standardised look worldwide thanks to Harry Beck’s 1933 London Underground Map, each rail line as a designated colour. However I’m not making a rail system I’m designing a Megadungeon! So I propose to make an elevation colour meter to give a sense of what level the routes are. I may make an isometric map once I get enough points created

As you can see from the maps above the region map will represent eight levels. Now the colour of which it intersects with a Burrow can indicate how many levels it has. Take Silkdown. It has a Level 1 and 2 major route. So it would be safe to say that it has at least two levels, although this is not always the case. Following the Level 2 route from Silkdown it suddenly raises from level 2 to level 6. This could indicate an elevator, stairs, shaft, or a sloped raise from 2-6 without any exits between the other levels. I will be including some dashed and dotted routes to indicate lesser used to secret routes.

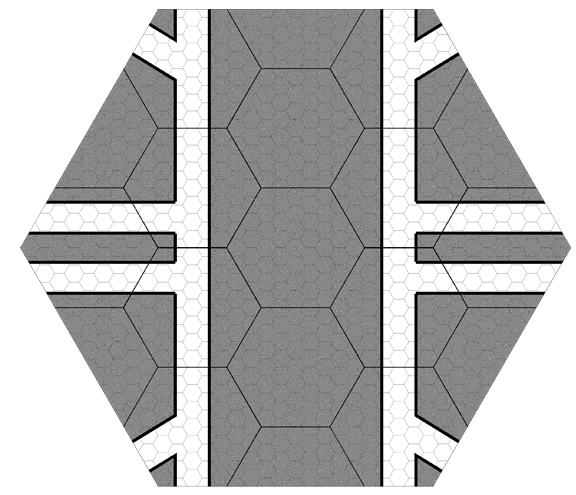

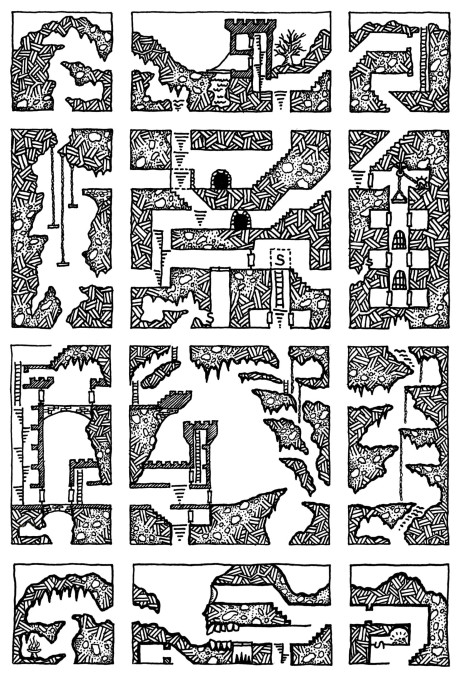

I’ve kept a hexagon grid system on the regional map so that I might scale in to more detailed areas (see image below) I will also be able to link up other regional maps in the future to this one thus increasing the size of the dungeon. Whatever scale I end up with will be in some way able to scale perfectly with my 7″ modular tiles so I can make some modular dungeon on the quick and slot them in.

Encounter Areas

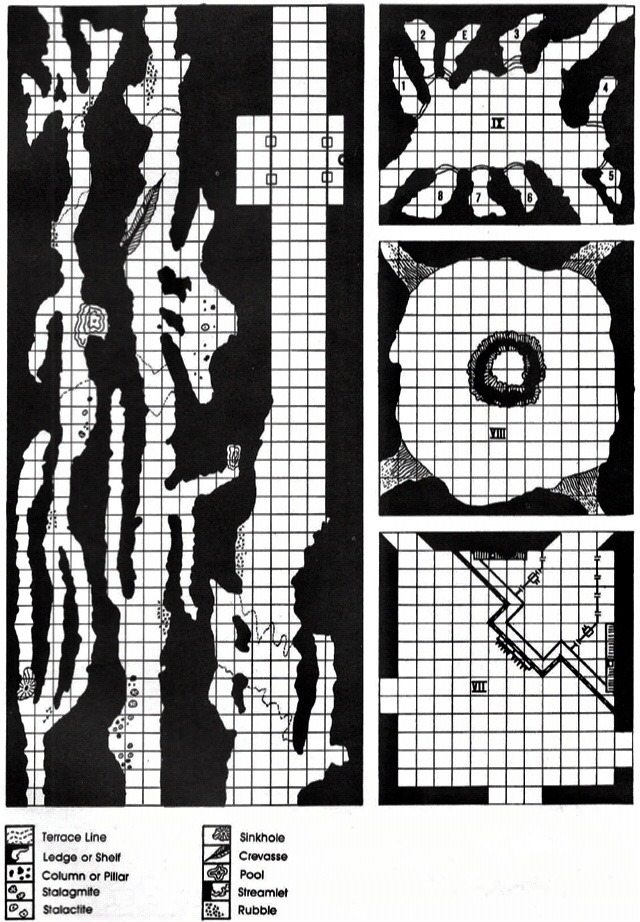

Encounter areas can be anything from a point of interest, to something special about the passage, to a small series of rooms, to a full blown dungeon area. Again this is a concept utilized by Gary Gygax in 1978. I like this idea as it allows the players to travel farther afield without having to map out the entire four day journey which would bore even the most OCD of gaming mappers.

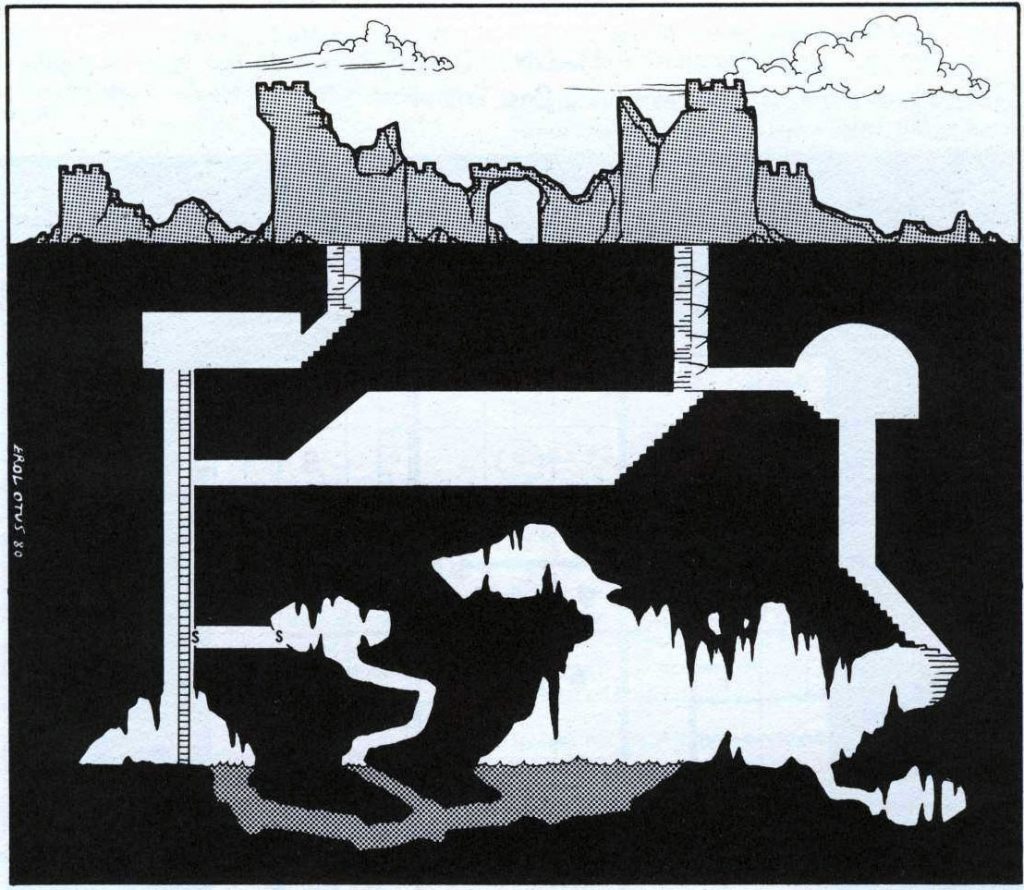

Another way of showing depth and scope, other than 3D modeling everything or isomorphic mapping, is to use a 2D side view. About ten years ago this became quite the craze kicked off by Stonewerks’s and Dyson. It became so popular that Profantasy even made a mapping anual for vertical dungeons in 2011. My first introduction to a vertical dungeon map was in 1981 with the vertical map in the D&D Basic book. I stared at this picture constantly and tried my hand at drawing my own.

Honorable Mentions

I should point out that there is Node Based mapping for megadungeons.

Melan on the Darkshire .net has a useful linear approach to mapping.

The Angry GM uses an encounter overlay based map, but different then the transit style. It certainly has its merits but I don’t think this would work for my own particular style.

I’m finding out that there are many ways to create an “overland dungeon” map, There isn’t a right or wrong way. Had I the skill or the time to learn I’d quite like to make a big old 3D render, but that isn’t practical. So for now I will stick with the abstract transit style map and use some vertical dungeons for a quick overview of larger areas that don’t need to be fully explored. No adventuring party walks into a small town and immediately starts to survey the entire place. They go to the inn and the shops and the rest of it is just decoration.

I hope you found this an interesting read, if you have any suggestions please make a comment!

Inspirational Links

Dungeon Fantastic

Greyhawks Underdark

Raging Swan

Grognardia

Dyson Logos

Stonewerks

Angry GM

“If you read the multitude of blogs out there Megadungeon campaigns rarely last for more than a year or two before either the players get bored or the GM gets burnout.”

I’d actually amend that to “If you read the multitude of blogs out there campaigns rarely last for more than a year or two before either the players get bored or the GM gets burnout.” For all that “megadungeons get boring” is perceived to be a thing, so is “campaigns get boring.” I’ve heard so often that D&D and AD&D have a sweet spot in the 4th-7th level range, and I think that’s more because that’s where games tend to run down and end, not because the system runs down and ends there.

Anyway, a helpful resource for you would be David Pulver’s article “Super Dungeons” in Pyramid 3/50, as is the AD&D Dungeoneer’s Survival Guide.

(I posted this before, but I was trying to use strikethrough HTML and it was stripped out. I edited to have it make sense without it.”

I do agree with you, and that is a much better way of expressing it. Thank you for the reminder of Pyramid 3/50. I don’t think I’ve read it since it came out in 2012 (where does the time go?). I will delve back into some of the pyramid articles and see if I have any from the saved web version that can assist me as well.

I’m planning on writing a short post focused on design aids, such as the Dungeoneer’s Survival Guide (one of my few books to survive a burglary 25 years ago), “Through Dungeons Deep: A Fantasy Gamers’ Handbook” by Robert Plamondon, Signe Landon, as well a few others.

I have a few ideas as well on how to keep things fresh. I’m playing in a home brew system that has lasted over ten years, and i’m hoping to use some of what I learned in that group and incorporate in in my new group. However they are a different type of gamer. More Role playing, politics, and intrigue over munchkin treasure grabbing.

The key, really, is that you keep giving your group what they want. My game has no plot, no politics, no story, nothing that isn’t just humor and grabbing treasure and exploring tunnels.

It’s been going 9 years now.

I could add more, but it’s possible the weight of the additions will overwhelm the joy that simply treasure grabbing and exploration doesn’t do.

It’s really the secret to all campaign longevity, really – it has to keep being fun. I’ve been able to find the source of fun for us. I’ve said this many times, but it’s true – this was originally a campaign meant to entertain us until we decided on what else to play. Clearly, we’re okay with this . . .